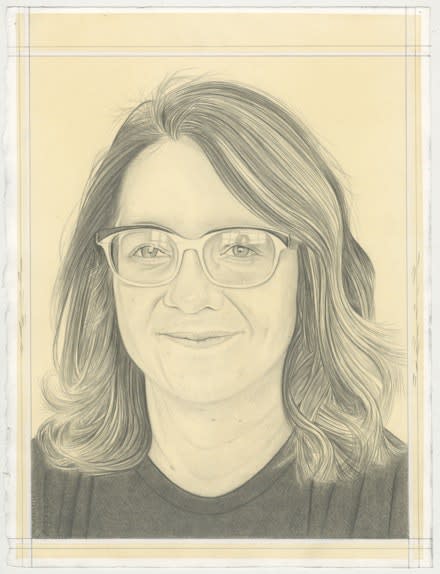

Gina Beavers was born in Athens, Greece, and currently lives and works in Newark, New Jersey. Her paintings capture an obsession with social media and YouTube’s curations of food, makeup, and the body, as well as online representations of fan, maker, teacher, and self. Beavers’s work is irreverent and visceral, composed of many thick layers of acrylic medium, pigment, glass bead, blue foam, and acrylic paint—yet they originate from the flatness of photography.

Beavers’s interest in “what is real” in art-making and image-making extends to her wish that artists know what is up in a larger sense. During the #J20 Art Strike in 2017 at the Whitney, Beavers said:

“Artists need to read critically—figure out how their passions are being turned on and off like a faucet—learn about history—learn about what is happening in the world and not just when it intersects with our lives—read opposing viewpoints—we need a Civics 101 class for artists cause we got played in 2016.”

Beavers has a BA in Studio Art and Anthropology from the University of Virginia in 1996, an MFA in Painting and Drawing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2000, and an MS in Education from Brooklyn College in 2005.

Her work has been presented in solo exhibitions at galleries including Michael Benevento, Los Angeles; GNYP Gallery, Berlin; Carl Kostyal, London; James Fuentes, New York; Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York; Cheim and Read, New York; and CANADA, New York, among others. In March 2019, MoMA PS1 opened Beavers’s first solo museum exhibition, Gina Beavers: The Life I Deserve, which is accompanied by the artist’s first monograph. Her work has also been included in group presentations at Kentucky Museum of Contemporary Art, Louisville; Nassau County Museum of Art, New York; Flag Art Foundation, New York; William Benton Museum of Art, Connecticut; and Abrons Art Center, New York.

Gina Beavers’s solo presentation, World War Me, is currently at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York through October 17, 2020.

EJ Hauser (EJH): I wanted to start with World War Me. Tell us about your title.

Gina Beavers (GB): Yes, there's a meme, a joke, actually, by a comedian I saw on Twitter—Matthew Ray—and it's a picture of Sarah Jessica Parker from Sex and the City, typing and in her kind of inner monologue that becomes the narrative of the show, saying: “As the world was on the brink of World War III, I thought, was it time for World War Me?” Which is kind of a very classic style of phrase for her. I thought it was such an amazing joke and so relevant to the time that we live in where we're really looking inward, and yet we have all of these external things happening outside us constantly. And this mash up between the world and global events, and then the incredibly personal, intimate details of people's lives. Like going through your phone and you're seeing global upheaval next to a cute picture of someone's dog. It's literally the global and the intimate on the one hand, and then on the other hand, it refers to a lot of different bodies of work within the show. There are different threads going through it. It's sort of me at war with myself as a painter.

EJH: Let's take a look at one of your new pieces, I would not call these traditional kinds of painting, they are very three-dimensional. Would you introduce us to how you build your work?

GB: For a long time, I've been building using very thick acrylic medium, it's basically acrylic paint with or without pigment, so that surfaces appear three-dimensional. And then more recently—because I had made a few that were, say, six by six feet, just acrylic paint that weighed hundreds of pounds—I started to incorporate foam in the larger pieces to make them a bit lighter—and the foam allows a lot more dimension as well. And, the larger foam pieces have more relief in them. I think initially I had started working with relief as a way to make photorealistic paintings, and to insert an element of unpredictability. I wasn't going to project a photo and paint it—or, paint it exactly. I now had to contend with the surface of the painting as this challenge that I had to overcome in order to render something. But I'm always trying to get sort of back to the original photograph. So, this one is kind of an offshoot of a bunch of paintings that I've done of lip tutorials. But now I'm painting my lips rather than appropriating images from the internet. And I’m painting a Jackson Pollock, or a Franz Kline, or an Ellsworth Kelly on my lips and then taking photographs and then making Photoshop collages. The finished lips are not super well painted because the originals were actually painted on my lips.

EJH: Something that I love about The Artist's Lips with Pollock, Kelly, and Kline (2020) is how it's funny but there's simultaneously a reverence for art history. And, I feel like much of your work has this beautiful way of upending the myth of male heroic painting. Is that idea in your head while you're making it; or after you've made it? And tell me how you see your relationship to this irreverence, this humor, this criticism that you're giving to art history sometimes, and the connection to the internet. I feel like I'm trying to dive into everything at once.

GB: For sure. I think a lot of the works that I have made that reference art history—like whether it's Van Gogh or whoever it is—have a duality where I really respect the artist and I'm influenced by them, and at the same time I'm making it my own and poking a little fun. And so, a lot of these pieces originated with the idea of fan art. You'll find all sorts of Starry Night images online that people have painted or sculpted or painted on their body. It comes out of that. And I just started to reach a point where I was searching things like “Franz Kline body art,” and I wasn’t finding that, so I had to make my own. Then it started to get a little bit geekier. I have a piece in the show where I am painting a Lee Bontecou on my cheek, that's a kind of art world geeky thing—you have to really love art to get it. And I'm not going to find it online—it's not a pop cultural moment where everyone's painting that on their face. I mean with makeup, and the whole conversation around femininity and makeup—I think for a long time when I was making makeup images, there were people that just thought, “Oh, that's not for me,” because it's about makeup, it's feminine. But it’s interesting, the culture is shifting. I just saw the other day that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did a whole Instagram live where she was putting on her makeup and talking about how empowering makeup is for trans communities. I'm interested in that, and lips are very symbolic in terms of femininity.

EJH: I sort of assumed that these are women's lips, and now that I know they're yours, that's confirmed, but, there is a kind of gender ambiguity to these pieces.

GB: Absolutely. Well, not to go too far into it, but within the whole world of makeup and this huge business that makeup has become, between Kylie Jenner and Rihanna’s hugely successful makeup lines, a lot of those techniques, contouring, and things like that do come out of drag culture, and how to really “make-up” your face. Even when I've been working from images online, I don't necessarily know the gender of the person in the picture.

EJH: We are both Gen Xers, so one of the things I know about you is that when you started making artwork, you were making artwork in a pre-digital, pre-internet kind of age. And I think that you've got—or at least the way I understand it—a very intuitive and thorough way of researching your subject matter via social media and internet platforms. Would you say that the way that you researched image-making in a pre-internet era had similarities to the way that you do research now?

GB: You know, it's really funny. I would take copies of the Village Voice—I lived in Virginia, in Charlottesville, but I got the Village Voice, the physical newspaper delivered to me—and I would go through there, and any images I could find in the newspaper I would take. That part of it, looking at media and repurposing it, has remained pretty constant.

EJH: Do you still have these ’90s source books?

GB: I still have some of the works themselves, and I might have some boxes of cutouts from the Village Voice and different things that are from the local paper newspaper. It's crazy to me. There has been such a resurgence within painting, if you look at the last 20 years, and a lot of that has to do with the wide availability of images online. If I wanted to paint a figure, I had to find an image in a newspaper, maybe have someone sit for me. But now it's like, you can just go online and find almost any position of a figure, you have so many possibilities. The availability of images has definitely changed art making, and painting specifically.

EJH: I have a question in relation to what you just said about using source materials. How do you go from the flatness of the digital image into thinking about the image as three dimensional? I mean, we all know what french fries look like, but there's still so much information there in terms of the three-dimensionality of it.

GB: I just draw it out, and then I have a way that I can see depth in a certain way, the way that you would just draw in charcoal, but I do it in three dimensions with the acrylic. I do have assistants that help me on these larger pieces. And it's very much an apprenticeship thing where I'm trying to teach them how I see things. It's very hard to teach things like, “Well, this is this depth and oh, this is this depth.” When I took my middle school tests or whatever—my high school tests, I placed really high in spatial, visual-spatial, whatever that is—and they were like, “You should be an architect!” So, you know, that was the acceptable thing you tell parents of creative kids, you know? “I want to be an architect!” So I have some innate sense of space, I don't know if that answers your question—but, it starts with a drawing, I grid it out, and then it's a lot of going back and forth between the original photo and what I'm working on. And I'll literally put a photo of the piece I'm working on next to the original photo on my phone and just flip back and forth madly, to get the sense of how close I am getting.

EJH: It's not like there's a tray with a couple of burgers and fries for reference in the studio. It's really coming from you matching your source photo to the photos of your work in progress.

GB: Yes, and trying to read the depth of something.

EJH: In-N-Out Burger! [Laughs]

GB: Yes. [Laughs]

EJH: About “in and out,” one of the things that I think about with your work are these complex threads that surround eating, food, the body, desire, sexuality, and being a woman.

GB: I want to applaud you for pointing that out because I literally never made that connection with the title “In-N-Out.” I thought we were going to talk about how burgers can be problematic, but that's amazing. I hadn't thought about that. I think there's a certain era with my work where I have a lobster roll, an In-N-Out burger, I have chicken and waffles, and different food culture things that were very buzzy 10 years ago. Things that were kind of innovative in terms of dining out—foodies have sort of taken over the world. These are just like little moments from that, I think. That question of the body and food, is super interesting. I'm not exactly sure, but at the time that I was making a lot of these—and I made a ton of meat paintings—I was vegan. It's not like an overtly personal thing, but there's definitely something there. As an American, food and body, those two things are just fused, right? I mean, in our minds, our body image, our consumption, our starving ourselves from gaining too many pounds, we’re being constantly assaulted with that. So that could be part of it.

EJH: And related to the three-dimensionality of this piece, I feel like there's a kind of question about, “What is distortion? What is cropping? How much information do you need visually to recognize the images that you're presenting?”

GB: I think one thing that occurs to me when I'm looking at these in terms of depth is a certain kind of photography where the camera is angled from a certain position from your body down—there are all of these kinds of camera angles that are fairly new, in terms of the history of photography. With the lobster, it's also this kind of this alien form. But also, again, very self-congratulatory, right? You're like, “Man, I'm loaded because I'm having this feast.”

EJH: Right, the lobster signals class and privilege too.

GBE: Yes, and it's also fun to paint. It's fun to try to conquer this really complicated subject.

EJH: How big is this piece?

GBE: I think maybe the long side is two feet—or maybe it was 16 by 20. Something like that.

EJH: What were your first forays into doing relief-like work? What did that look like when you were first starting out?

GBE: Well, I used to do flat, abstract work that had very hard edges. And I had seen this sample sale of T-shirts, graphic tees with amazing designs and patterns on them. They were abstractions, done with a screen printer. It was a “what am I doing?” moment. I'm just making something that could be screen printed. So, I started to think about wanting my work to be more handmade. I wanted it to look like it couldn’t just be made on a flat machine. Art Guerra was in my studio building and he worked at Guerra Pigments and he started bringing me a bunch of acrylic so I started experimenting with the acrylic, but it was still very much in the realm of abstraction, but just a little bit of the three-dimensional. Maybe there were some textures that were built up or sometimes I would put the acrylic down flat and peel it—you could paint on it and then stick it like stickers—those kinds of experiments. And then in 2010, I started to see a lot of images in my feed of food. And I was really drawn to images that were more abstract, like Chuck Webster—shout out: great painter and a great cook!—he took a photo of a plate of short ribs he made, it looked abstract—and I made a painting of it. I think that was maybe my first one.

EJH: I know you are interested in the idea of artists utilizing, for lack of a better word, failure. The idea that no one is going to teach you how to paint like Gina, except Gina. Is this journey a kind of process of elimination—plus, a wanting to go towards something?

GBE: It's interesting. I have a friend who has worked for a lot of artists and she said that that's always the thing where an artist will say, "Okay, well, we're gonna do this thing. This is not how you normally do it, but this is how I do it." And it will always be a process that the artist has kind of pioneered or engineered themselves. So yeah, I identify with that. I really like the tactility of this material, and I want to use it, but there's definitely times when I run into technical issues, and I don't know who to ask, because even the people that make the material don't really use it in a certain way. You're sort of left to test things and be more like a scientist, and ask, “Is this going to hold up?” I have to do a lot of that. And then over time, keeping an eye on them. How is it aging? What are they doing?

EJH: I love the idea that your paintings are created using a specific recipe, and then you serve us up your visual ideas.

GB: The thing about a recipe is that idea that you sort of get in there and you hope it's going to turn out a certain way. But when you're in the middle of it, you're kind of putting things together and being like, “fingers crossed.” This image was interesting because it came out of this era in 2015 where I first started to notice while looking at images that it was difficult not knowing if they were real or not real, and starting to see the effects of Photoshop and memes, and this distrust of what's real, what's not real, which I think has just accelerated over the last five years.

I'm interested in photorealism, partly because of the way we live—right now, I'm looking at this screen and technically these are photos of all of you guys. We are living in this other world which is pretty much dominated by photography, and I'm interested in a photographic light. I like the glare of things and I want the work to refer to that second life that we live. Not in our real world but the online world.

EJH: Do you think your work takes a position about the online world? Or challenges that world? Criticizes that world? Pokes fun at that world?

GB: I think more just to document it in the way that you would document the real world. Just like the way you go sit in a field and paint a landscape, it's like that but just for the internet, or just for that world.

EJH: Wow, I love that answer. [Laughs] Let's look at another one. This is Hand Bra from 2015.

GB: This is from that same series of images that are real and not real. It's a real bra with fake hands that look real on a real body.

EJH: And this is a bra that one could buy on the internet, correct? And these seem to be fake male hands holding onto the outside of this bra—I guess it’s intended to be both sexist and funny? I've been thinking about being a woman in 2020, and being an artist, and the kind of availability that we have in using women's bodies that maybe guys wouldn't… Do you think women have a unique opportunity right now to rearticulate spaces of sexual imagery or sexy imagery?

GB: I've said this before, we spend potentially a lot of our lives being sexualized, whether we want to or not, from a young age comments are made—it’s pretty nuts when you think about it, particularly when you compare it to a boy’s experience growing up. We should be able to use it however we want. I have a sense about how far is too far, an internal sense, but I also feel like we can joke about it in the safe space of a painting. We can joke about these things, or I can make jokes. I have a painting in my Boesky show that is a very anatomically correct vagina-burger. I think it's funny. It's irreverent in the sense that finding a vagina online that is full frontal that I can work from, is a whole kind of political situation, and hard to find. They're photographed enticingly but demurely a lot of the time, or it's just from straight-up porn, which is its whole own kind of culture and economy. So even just finding that image to work from… and then what would the objection be? That it's too explicit; that I'm somehow denigrating the vagina by making it silly or something? Our bodies are silly—not just our bodies, but everybody's bodies.

EJH: I'm thinking about when I spoke with Judith Bernstein, and how people were so upset about her using phallic imagery—and how this is an overgeneralization and unfair, and male artists have been using genitals however they want in art-making forever, and then women—whether they're using dicks or vags—it's like they shouldn’t use either.

GB: First of all, let me say Judith Bernstein is the inspiration behind my vagina-burger, because it's large scale, and I was definitely thinking about her work. So, I want to give her a shout out. But, don't underestimate the power of controlling women's sexuality. I mean, it just happened, you know, “WAP” came out by Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion and there was just all of this conversation around whether or not they could do that and was it right, was it just like the fact that it's controversial that it was important? We're still dealing with this idea that we can't even own the representations of our own bodies.

EJH: When I was looking at this bra piece, I was reminded of the Sarah Lucas Self-Portrait with Fried Eggs from the late ’90s, of her in the t-shirt with the two fried eggs on each boob, such a favorite image.

GBE: Totally, and there are a lot of photographers and meme-makers and people who've done the eggs on breasts online and, you know, she deserves credit for that. She did it first, she’s really amazing.

EJH: And the expression on her face.

GB: She's wonderful.

EJH: I love your painting Smokey Eye Tutorial! Is it related to Sarah Huckabee Sanders?

GB: [Laughs]

EJH: Oops! I see this piece was made in 2014, that's before she was Press Secretary.

GB: The fervor over that joke which was such a perfect joke about her smokey eye. No, this was something that, around this time, started to appear in my feed. I got really into the idea that the painting is drawing and painting itself, while it's looking at you, it wants you to like it. So yes, that's where this whole body of work started, with this image.

EJH: I love that the makeup tutorials are about transformation, which I think is such a foundational part of understanding art-making.

GB: This gets back to the idea of the restaurant-goer with the camera. It is a creative community of people online as well, and I'm interested in their creativity, and the idea of this self-determination, and the self-making too, like, “I'm going to make myself what I want to be.”

EJH: And it's on YouTube, so you can learn how to make your smokey eye for free. It's a very democratic kind of proposition.

GB: Totally. Yeah, I really like that.

EJH: In some of your new works, you're breaking down the individual frames that separate the different stages of the tutorial. I’m remembering one that uses a pair of lips for the eye, and lips where the lips should go, and then there are also lips on the side of the face. All the action is taking place simultaneously inside one frame—there is an almost surreal quality to the image. What was your thinking for combining everything into one picture?

GB: One of the situations is that I'm moving away from found images and found tutorials and I'm creating my own. For instance, we looked at that black and white image with the lips. My whole idea with that composition was that it would be an all over composition, a classic kind of Abstract Expressionist image—I was playing with that. I have another one where I'm working with pink lips with Georgia O'Keeffe and I turn the lips so that they're more like a vagina—so I'm playing more and it's really just a function of me creating my own compositions. With the Lee Bontecou piece I am showing the tutorial step by step like a fan would—with more famous artists, I'm a bit more irreverent. I feel like I can play more with them because it's almost like work that's in the public domain. It so reproduced it’s fair game.

EJH: Working with other artists and referencing other artists is such a sincere gesture—I also love art in that fangirl way, and I often make secret homages to artists, embedded in different ways—this is something that the artists I know really play with.

GB: For sure. I love that—artists are the biggest fans.

EJH: Absolutely.

GB: Speaking of Artists being fans of other artists, when my dad was the American Consul in Toronto in the ’90s, he was helping Keith Richards get his visa to come to the States because he'd had all sorts of legal problems. And so, my dad hung out with Keith Richards in his car. He was playing his new CD, but he also talked to my dad about music. He had heard the new Britney Spears album. He had heard everything that was on the radio. He knew every single musical act in the world. He was just so obsessed with music, you know? I think about that, like, that's how you feel right? That's what's been so hard about this time without art—you feel like a half-person when you can't go see things.

EJH: When we had our phone call the other day you were saying that, usually, going to the studio is so joyful and fun—and I know you keep a pretty regular studio schedule—but since the pandemic you are just mostly in the studio working, and that getting that balance has been complicated.

GB: I used to keep regular hours, and I was thinking about Zadie Smith and her book of essays, Intimations, which is really wonderful. She talks about her writing schedule being sort of laid bare to her family, and her family actually seeing this insane way that she lives her life, by segmenting it into these blocks of time, and it's funny because I feel the same thing. I used to work 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., but now because of the pandemic, because my husband's home, and we don’t have a lot of interaction with people, I feel a real need to come and see him and he's the only other real person I could hang out with regularly. So, I may still work a lot, but I've shifted my priorities in a certain way. It’s completely changed the way that I organize my time.

EJH: Let's look at Burger Eye from 2015. Was this one of the first works where you cross-pollinated or melded your ideas about the body and food?

GB: Yes, I think so. I've started to do that a lot more where I'm referencing a kind of cross-pollination, and I think of it as that way you spend half your time online or on social media, looking at yourself—I hope I'm not the only person that does that—the space is also about the way we’re constantly looking back at earlier work or earlier versions of ourselves. This was at a time when I was super fascinated with makeup and all of the kinds of costume makeup and things you can find online that go away from a traditional beauty makeup and go towards something really wild and cool.

EJH: So, about these nails in Dice Nail Love (2014)—they're little canvases, right?

GB: Yes, totally. When I made this one, I thought this was really deep because it's like, “a roll of the dice, it's fate—what will happen?” These deeper philosophical issues kind of melded with the nails. I thought that was interesting.

EJH: When you think of your nail pieces, do you think of them belonging to different hands? Are they your hands? Or do they just come from the internet, and that anonymity is an important part of the piece?

GB: I think there's always, with all the pieces, a biographical element to them, an autobiographical element, even though they may technically be other people's hands. There's something that I'm thinking about or that I relate to. So, it's kind of both. But this idea of holding something and just the wild opportunities for nail art that exists now, it's really fascinating.

EJH: I like how you describe your process of collecting images, that you're not always sure why you're grabbing them. That you kind of collect first and process later.

GB: Yeah, I definitely do that. I collect images and then go back and think about what is meaningful—because I've had this thing where I gravitate towards images that are aesthetically really interesting, but also have a narrative that's really interesting. For me, they have to have both. And then whether or not that narrative is interesting to me or relevant to me in some way where I can understand it on a sort of subconscious level—that's the process. And more recently, I’ve been creating more of my own images by making photo collages. Like the eggplant nails piece, which is my hand… I'm starting to make my own images.

EJH: Do you see these photo-collages as almost forms of drawings?

GB: I guess so. Yeah, they are. I spend a lot of time on those and take hundreds of pictures and do little shoots—so they kind of are.

EJH: And some of these, especially some of the nail pictures have a feeling—like when you go to the state fair and you look at cakes—and generally all of the cake decorating that's currently going on in popular culture.

GB: Yes, for sure, cakes. I have made a bunch of cake tutorials, cake body tutorial paintings, as well, because I think that's super interesting—that whole creative community and all the shows, like reality shows. There's Cake Boss—actually we watched Nailed It on Netflix with Nicole Byer and I'm like, “I think I could do that,” because that's a lot of fondant and a lot of sculpting and stuff. I wonder if I could do that cooking show just because of the kind of work I make.

EJH: I can't wait to watch that show, Gina. [Laughs]

GB: Thank you, EJ. I really appreciate it!